Rock or frog? Frog. Rock or frog? Rock. Rock or frog? Two frogs.

It’s a Monday night on the North York Moors. The landscape here is fairly featureless on the brightest of days, which means there’s even less to distract you in the dark hours of the night. Except for the frogs. And the rocks. They are keeping me sane, although I’m not quite sure how I ended up here in the first place.

From the moment I left St Bees on Saturday morning, my race has already been nearly over a couple of times. It was all going great at first though. There was the unexpected friendly face helping out at registration (Joanna, ex-KWU), the usual sleepless night, a small pebble picked with Irishman Shane to carry to the North Sea, my back taped perfectly by Karola who I’d met the night before <insert some hashtag about women helping women> and the prospect of running straight into storm Kathleen. I didn’t quite know what to expect, but somehow I felt ready. With most of my training done in lovely Kerry conditions, I wasn’t too worried about the wind and rain.

The Northern Traverse is a 300 km coast-to-coast route, crossing the north of England through three national parks: the Lake District, the Yorkshire Dales and the North York Moors. The Lakes is the highest part of the course, which coincided nicely with the named storm that was expected for day 1. It was a very mild day though, so the wind wasn’t too much of an issue at first. We even got some tailwind during the first 30 km, a flat-ish warm up before we’d hit the mountains of the Lakes. The only issue was the mud on off-camber fields, making it awkward to stay upright. Some of the trails in the Lakes had turned into streams, but I wasn’t expecting to keep my feet dry anyway. I was enjoying the views and the chats with people who hadn’t a clue what I was saying (and vice versa). Not a care in the world. I stopped for a short chat with two friends from the Netherlands who happened to be in the Lakes that weekend, before heading into the first checkpoint in Borrowdale. My plan was to make the most of daylight, so I just grabbed a bit of food and was on my way again. There’d be plenty of time on the next climb to eat and hike. I love the Lakes; this was awesome. Soon the weather started to turn though. The wind got even stronger and the rain was getting more serious. I was half excited – I’d been waiting for this.

The excitement didn’t last too long. On the descent past Grisedale Tarn I got very wet, not because of the rain but because the wind was sweeping the water out of the lake. Most of us lost at least one of our race numbers here – I don’t think anyone reached Robin Hood’s Bay with their numbers still attached to their clothes or their pack. Coming into Patterdale, we were informed that we’d be diverted onto the bad weather route, meaning we wouldn’t be climbing Kidsty Pike and we’d be following a lower level (and slightly longer) route instead. I’d studied the main route in detail, but since the gpx for the diversion had only been shared with us the day before the race I hadn’t had the time to take a proper look at it. I finished my chips and tea and hoped for the best.

Unfortunately the file wasn’t very accurate (or at least that’s what my watch showed) and it was near impossible to find the right trails. After my third wrong turn some guys caught up with me who were doing the shorter Lakes Traverse. They were also a bit lost, but at least they were in much better spirits. One of them spoke some broken Dutch and the jokes kept us all entertained while we tried to figure out where we were supposed to go. Just as it was getting proper dark, we were on some more defined trails. This is also when the weather took another turn for the worse with heavy horizontal rain and the wind trying to sweep us off our feet. The guys disappeared into the distance and I started to realise I should be wearing more layers. With absolutely no shelter it was impossible to get anything out of your pack though, so I decided to keep moving and make it to Shap as fast as possible. I wouldn’t have my drop bag there, but I’d be able to get all my kit out of my pack and put it on without half my stuff getting blown off a hill. Shap turned out to be further away than I thought and when I finally arrived at the checkpoint I was wet, cold and miserable. I felt incredibly stupid but as it turned out most runners arrived there in pretty bad shape. Nothing that a nice cup of tea and some soup with rice couldn’t fix.

After Shap we’d be heading into the Dales, the part of the course that I was least familiar with. I was nice and warm now in my waterproofs, although I struggled with navigation. It was a never ending series of muddy fields and boggy hills that had to be crossed. Usually there’d be a gate on the other side that you could aim for, but the combination of darkness, rain, hail and winds that were trying to blow your eyeballs out made it hard to spot anything at all even if it was right in front of you. Thankfully I was able to team up with a few others for the last couple of hours before Kirkby Stephen – there weren’t many words said, but working together made navigation more manageable for everyone.

We arrived in Kirkby Stephen around dawn and I was delighted to be reunited with my drop bag again and pick up my earphones. Some music would do me good, I’d had enough conversations with myself at this point. As soon as I sat down though, I could feel I was getting dizzy and lightheaded. I alerted one of the volunteers and before I knew it I was lifted off my chair and put on the ground with my legs up. A bit more oxygen in the brain instead of the legs, some tea and a sandwich, and all was well again.

As I left Kirkby Stephen, I was on my own again. I knew it would be a fairly long climb up to Nine Standards followed by a section with plenty of bog, so I didn’t mind doing that in daylight. During the climb I noticed I was getting sleepy but just when I thought I’d need some caffeine, the terrain got more exposed and I nearly got blown over. Perfect, that would definitely keep me awake for the time being. The people who’d warned me about the bog after Nine Standards had not been exaggerating. There was a bit of a trail you could follow, but it was a constant challenge to not sink down too deep while also battling 80 km/h headwinds. The further I got into the Dales, the more I started to suffer from pain in my lower legs. When you’re out for 24+ hours there are always going to be aches and pains that come and go, but I could no longer deny that the pain at the front of my feet/shins was only getting worse. My run turned into more of a hobble and even though I still tried to make the most of any flats and non-technical downhills, I noticed that I was slowing down considerably. I think it was actually quite a nice section with some lovely green hills and old mining stuff. It just didn’t really register with me as I was slowly entering my own little world.

By the time I reached Reeth, I was having some serious doubts about the state I was in. I tried to put it down to lack of fuelling even though I’d been eating well. Reeth had a small checkpoint with lovely people and good snacks so I spent a couple of minutes there to get sorted. I met Gillian who was running the Dales Traverse for her 50th birthday. She offered me a hug, one of the best hugs I’ve ever had, and we left the checkpoint together. I decided to continue on to Richmond and reassess there. Gillian went ahead to run at her own pace and I was soon caught by Eoin Keith. We shared a few miles and though the chats were good, I was unable to keep up with his hiking pace – or the hiking pace of any of the others who followed. There was a short conversation with Glenn from Norway where we both pondered the idea of making friends with the pain. I told him I’d tried it, but that I tend to actually like my friends – and the best I could do with this pain was tolerate it. Glenn was walking too fast for me and I was getting passed left and right by the back of the pack of the Dales Traverse now who’d started their race that morning. By the time I reached the final road section into Richmond, I was completely demoralised. So far I hadn’t looked at my pace at all, but now I felt like I needed to know how bad it really was. Give me some numbers. My watch told me I was walking 20 min/km… on flat road. I noticed I was getting cold as well, even though I was wearing all my layers.

When I finally reached the checkpoint in Richmond, I was 99.78% sure that my race was over. I drank some tea and tried to eat some overly spicy curry while explaining to the medics that no, the fainting was no longer an issue, I just wasn’t able to move my feet anymore. They were pretty much stuck in a 90 degree angle, making it very hard to do any type of walking or running motion. A quick examination put into medical terms what I already knew: both my legs were a hopeless mess. Tibialis anterior tendonitis. This wasn’t just discomfort, this was pain – and as a rule I don’t push through pain, since it’s usually a sign that something’s actually wrong. Rules or no rules, this tendonitis was either going to slow me down tremendously or end my race altogether.

All goals were out the window and it was up to me to decide whether or not I wanted to commit to a slog to the finish line. In hindsight I think I’d already used the hours in between Reeth and Richmond to make peace with the fact that I wasn’t going to get the result I wanted. And I wouldn’t be leaving Richmond anytime soon, that much was clear. I’d be going too slow to keep myself warm during the night and I wouldn’t be making much progress anyway. I decided to divert from my original plan entirely and go for a proper sleep – maybe the tendons would settle a little bit overnight and maybe, maybe it would all look much better in the morning. I started getting some messages from concerned and/or annoyed dot watchers, but I ignored most of them and crawled into my sleeping bag with an alarm set for just before sunrise the next day.

That morning I had some difficulty getting out of the cold tent but as I was walking to the medic, I realised I was in fact walking. It wasn’t smooth or pretty, but it was better than it had been the day before. The medic was realistic: the tendons were still very angry, they’d heal with rest and continuing to run/walk on it would only aggravate it even further. I wouldn’t be doing any long-term damage though, it would just take me longer to recover from it afterwards. Ultimately it was up to me to make a decision: pull out of the race for a perfectly valid reason and be back training the next week, or keep going at a much slower pace accompanied by my (not-)friend pain, and risking several weeks if not months of recovery.

As much as I like to get back to my normal routine as quickly as possible after races, I knew I’d be kicking myself if I’d pull out of the race without giving it one last try. As I started packing my kit again, I told the team at the checkpoint that I’d just go out for a ten minute jog. If the pain would get progressively worse again, I’d come back and call it. They agreed to keep my drop bag there a little bit longer just in case. Katie, one of the wonderful volunteers who’d been helping me out, said she really hoped she wouldn’t see me again – one of those rare occasions where that’s the nicest thing someone could possibly say to you.

As soon as I was on the trail again, I managed to find a jog/shuffle type movement where I didn’t have to move my feet too much and could still get some forward motion. It hurt but it wasn’t as agonising as it had been the day before, and I felt like I was actually going somewhere. Surely I couldn’t turn back now, especially with the relatively easy section that was ahead of me. The Vale of York would be pretty flat and boring – I’d been dreading it while studying the maps beforehand, but at this point it was perfect for me and my mangled legs. I ran with Tim for a bit, started passing some people again and had some chats here and there, never failing to mention that Lordstones was going to be my finish line. Hills and technical terrain were just impossible with my very limited range of motion, so that made perfect sense. I would be at Lordstones before dark, pull out, get a lift to the hotel and be in Robin Hood’s Bay in time for dinner. Everybody would understand, I still would’ve put in a good effort and hopefully there wouldn’t be too much damage done.

Just like the rest of the course so far, there was plenty of sticky, sludgy mud between Richmond and Lordstones. I was a bit surprised when I started seeing blood in the mud, and it took me a while to realise that the blood was mine. Apparently I was having a random nosebleed and by the time I’d finally figured that out, the blood was everywhere because I’d been wiping sweat off and taking things out of my pack as well. Thankfully I was nearly at the A19 and there was supposed to be a Shell service station there. I made an effort to wipe my feet before I walked in (politeness is everything), but the lady who was working there made it clear that I had other things to worry about. ‘You might want to wash your face, love.’ When I looked in the mirror I could see what she meant. My hair looked like I’d been running in a storm for the past two days (which was true) and my face and neck were all covered in blood. As if I’d just wrestled, butchered and eaten a sheep with my bare hands.

After a much needed wash and a very careful crossing of the A19, it was time for the last push to my very own finish line in Lordstones. 15 km to go. I’d take on those last two hills before Lordstones just to prove that I was making the right decision and that it would be impossible and unsafe to try and cross the Moors. First hill: uncomfortable, painful, but not much more painful than what I’d already done. Second hill: slow, embarrassingly slow, but not much slower than what I’d been doing all day. When I finally looked up, I could see a hill in the distance with an all too familiar shape. Roseberry Topping. It had been ten years since I last saw that hill, and just seeing its Matterhorn-esque shape brought back all kinds of memories. They weren’t all happy ones – life has taken some unexpected turns since my time in England and getting to where I am now has been a feat of endurance in and of itself. Seeing Roseberry Topping made me realise that this race wasn’t over yet if I didn’t want it to be. The outcome would look differently, I wouldn’t get a finish time that I’d be particularly proud of and it’d definitely hurt. But if I wanted this to happen, I would make it happen. I’d surprised myself before, I could do it again.

And so just before I reached my finish line of choice that I’d been aiming for all day long, I moved the goalposts and started thinking of the actual finish line of the Northern Traverse in Robin Hood’s Bay. Before I had a chance to get too philosophical about it all, a boy came running up towards me. It was 14-year-old William, who told me about his running, his Hardmoors races and his big goals for the future. We chatted for a bit and it seemed like William knew more about ultra running than most of us who were actually out there doing the thing. The chat was nice but it also meant trying to keep the expletives to a minimum on the painful rocky bits, which was a challenge. I liked his positivity though so I soaked up his words of encouragement and off he went as I made my way into the checkpoint.

At Lordstones I rang my hotel to let them know that I’d be later than expected, I drank some tea and ate another load of chips while getting my gear ready for the night. I hadn’t planned to do a third night but in fairness it wasn’t really my third night, as I’d spent most of the second night snoozing in my sleeping bag. I didn’t know what day it was anyway, I just knew that Robin Hood’s Bay was another 65 km from there and it was starting to look like I might actually make it. I had some steep climbs and descents coming up. They wouldn’t be very long but I wasn’t sure if I’d be able to make any big steps up or down, so I let the volunteers know that I’d just give it a try and that I’d be back soon if I couldn’t manage. Since there was still a bit of daylight left I didn’t waste too much time and started the first climb. Pain was talking to me loud and clear but I was no longer listening. I’d discovered that one leg hurt slightly less than the other, so that was going to be my ‘good’ leg. Any big steps up or down would be taken care of by my good leg. In reality it didn’t make much of a difference, but the fact that I’d put a strategy into place gave me at least the illusion of control.

Darkness fell as I went over the last of the steep bits and as soon as the terrain got a bit easier and flatter, I started my penguin shuffle again. There was a light behind me of someone who was slowly catching up with me, and when he finally passed me it turned out that this man’s hike was faster than my shuffle. I didn’t mind. He taught me a few things about cows before he pushed on. This is when I started my game of ‘frog or rock’. There were lots of frogs jumping around the puddles, but on closer inspection some of them turned out to be rocks. Frog or rock? Rock or frog? It kept my mind occupied as I kept moving east and into bad weather again. What started as light rain quickly turned into heavy showers. It caught me by surprise and it was night 1 all over again. The storm was gone but it was still windy enough on the exposed terrain. I tried to put on my waterproof pants but the zippers were caked in mud as were my shoes, and I couldn’t seem to figure out a way to make it work. Standing still on the side of a hill in lashing rain didn’t seem like a great idea either, so shorts it was. It was wet, but not that cold. My legs have had worse.

The trails turned into streams again and the mud was what it had been for the entirety of the race: thick, sticky, slippery. As I shuffled into the last checkpoint in Glaisdale, the volunteer told me that everybody else had arrived there walking. I really wished I was one of those people who could still walk – I didn’t even sit down at the checkpoint because I was fairly certain I wouldn’t be able to get up again. Sandwich, tea, phone, bottles and off I went. Next stop: Robin Hood’s Bay.

They say misery loves company, but I was glad to be on my own for those final sections. I didn’t feel very human anymore and it was great to be able to make any noise I wanted without having anyone near me. Just before dawn I started seeing some things that weren’t actually there – signs for restaurants and alpaca farms, a trailer unloading an infinite amount of horses (they just kept coming) and a group of hikers who disappeared into thin air. I’ve always felt like a fake ultra runner with my lack of black toe nails and hallucinations so I was glad to tick that box now. The black toe nails can wait, that’s fine.

Up until that point I’d mostly just accepted the ground conditions for what they were, but during the final 20 km I got more and more fed up with the wet, the bog and the mud. I needed it to be over. As I reached the North Sea coast and turned right onto the cliff path, I looked ahead and lost all hope. More shin-deep mud, more short steep up and downs, more off-camber. It was like a depressing highlight reel of all I’d had to go through to get there. It was Tuesday morning now and I knew people would be watching the tracker from the comfort of their home or office, assuming I’d be finished soon. They’d be in for a disappointment. I was back to doing 20 min/km, desperately using my poles to pull myself through the mud and trying to focus on just one step at a time.

I may have scared a few tourists on my final descent through town as I tried to smile while all I could manage was to just bare my teeth. Some of the volunteers who’d been helping at the checkpoints were now at the finish and seeing them again meant a lot to me. They felt like old friends at this point. Joanna was there as well and I could barely believe it had only been a few days since I’d met her at registration where we’d promised we’d see each other again in Robin Hood’s Bay. You’re supposed to throw the pebble that you’ve taken from St Bees into the North Sea, but I just didn’t want to. It felt right to take the pebble home with me. One of the volunteers was kind enough to actually get me another one from the beach in Robin Hood’s Bay, so I went home with two small stones to remind me of this… let’s call it an adventure.

Although this race didn’t go to plan, finishing it felt like the right thing to do. I think pulling out at Richmond would’ve been perfectly acceptable and I don’t believe in the whole ‘death before DNF’ mindset. In this case, though, I think it was the right decision for me to push through the pain and take some calculated risks. I’m not too happy about the longer recovery time and one might label that as regret, but I know I would’ve regretted a decision to pull out just as much – just for different reasons. I think this was the right time and the right place for me to fight a few demons, remind myself of what I’m capable of and learn a thing or two about this type of distance as well.

I hope I’ve confused enough people with my accent over the course of the race, while also trying to educate them about Kerry (which is in fact in the southwest of Ireland). I won’t be complaining about mandatory kit anytime soon and who would’ve thought that training with a heavy pack will indeed make you better at running with a heavy pack… I was delighted with that.

Getting to the finish line was only possible because the event was extremely well organised and because I felt safe and looked after at every checkpoint. The volunteers were amazing and with most of them being runners themselves, they understood when you just needed some space. I also got all the help I could possibly ask for after I’d finished. I was a fairly broken woman for the first couple of hours and to have Eoin Keith help you take off your shoes and the race director take care of your feet is a little bit embarrassing and the best thing ever, all at the same time.

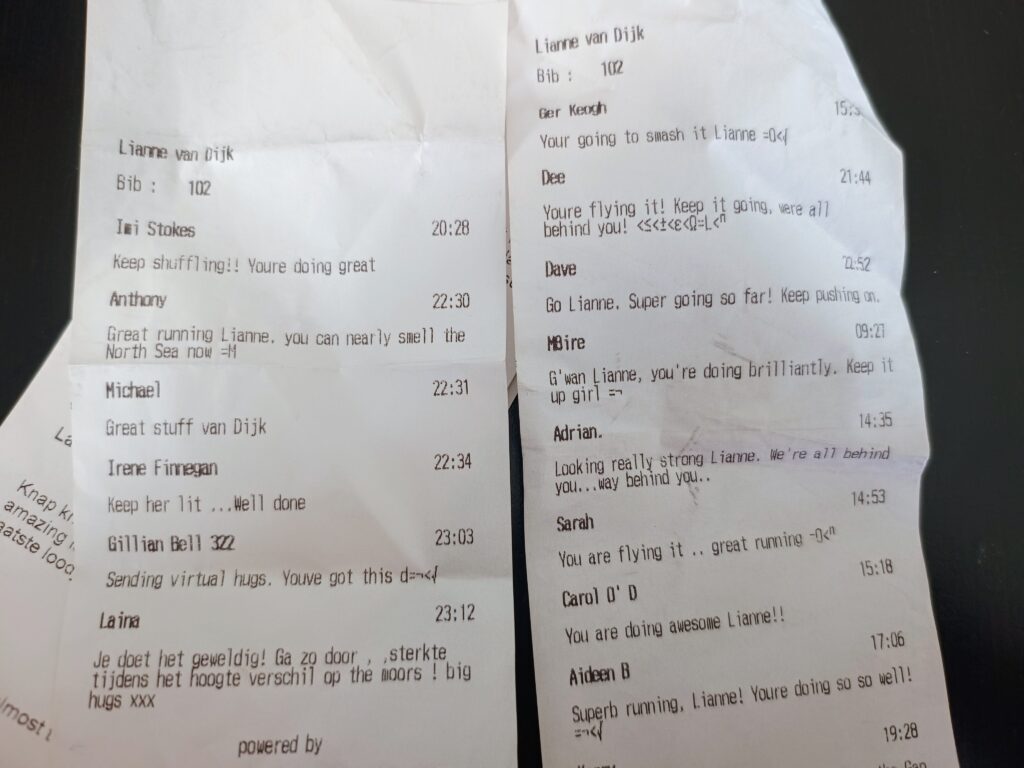

Thanks for all the tough love, kind words and (virtual) hugs. They gave us a print-out of the messages at some of the checkpoints, and the fact that most people just assumed that I’d keep going definitely helped me in my decision to go for that ten minute test jog in Richmond. And what a test jog it turned out to be.